Marijuana Statistics in the US: Cannabis Use & Abuse (2024 Data Update)

Report Highlights:

- 12% of American adults have smoked marijuana in 2021 [12].

- 52 million Americans will have consumed marijuana by the end of 2022 [20].

- 44% of American college students used marijuana in 2020 [28].

- 51% of Millennials have tried marijuana and 20% of them smoked weed [12].

- 10.1% or 2.5 American teens use marijuana illicitly [31].

- 15% of men smoke weed compared to 9% of women [11].

- 39 states now have legalized high-THC medical cannabis, including the District of Columbia [20].

- 19 states have legalized medical and recreational marijuana, including the District of Columbia [20].

- 74% or 248 million Americans now have access to some form of legal weed [20].

- 91% of American adults are in favor of legalizing marijuana use [9].

- 67% of physicians favor the nationwide legalization of medical cannabis [8].

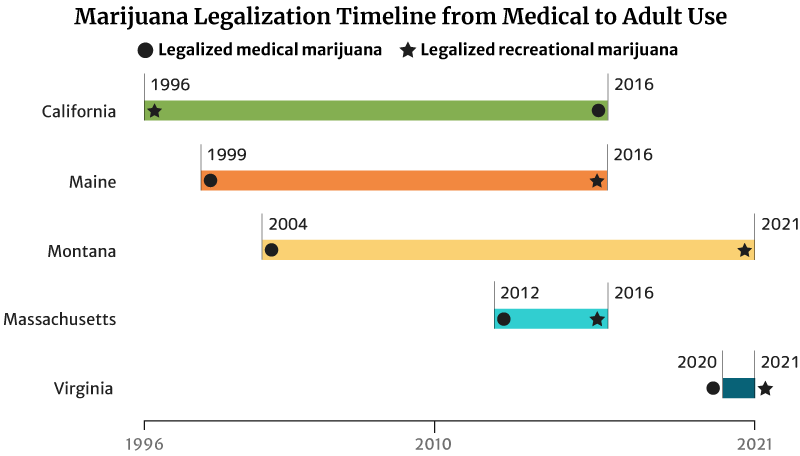

- The state with the longest legalization timeline is California with 20 years. Virginia has the shortest timeline of one year [20].

- Deliveries made up 60% of the cannabis orders in 2021 because of the COVID19 pandemic [2].

- California has the highest legal cannabis sales at $5.7 billion [1].

- U.S. legal cannabis industry could generate $32 billion by the end of 2022 [20].

The United States cannabis industry has grown stronger over the past few decades. It even surpassed expectations.

This U.S. marijuana statistics report shows you how the cannabis landscape has changed over the years. It will also give you a glimpse of its future.

How Many People Smoke Weed?

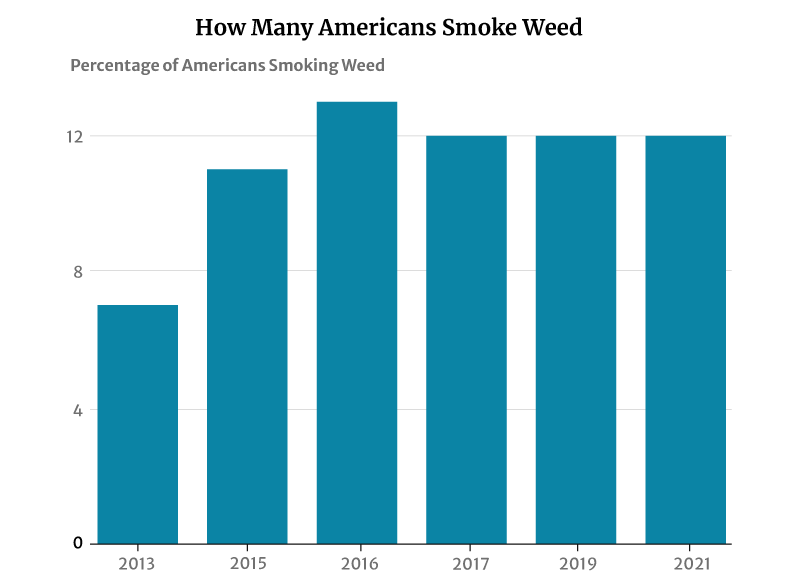

12% of American adults smoke cannabis, says a 2021 Gallup telephone survey [12]. This percentage has not changed much in recent years. It plays anywhere between 11% and 13% from 2015 to 2019 [1].

However, this has had a significant increase from 2013’s 7%. It was in 2013 that the number of smokers was initially measured [11].

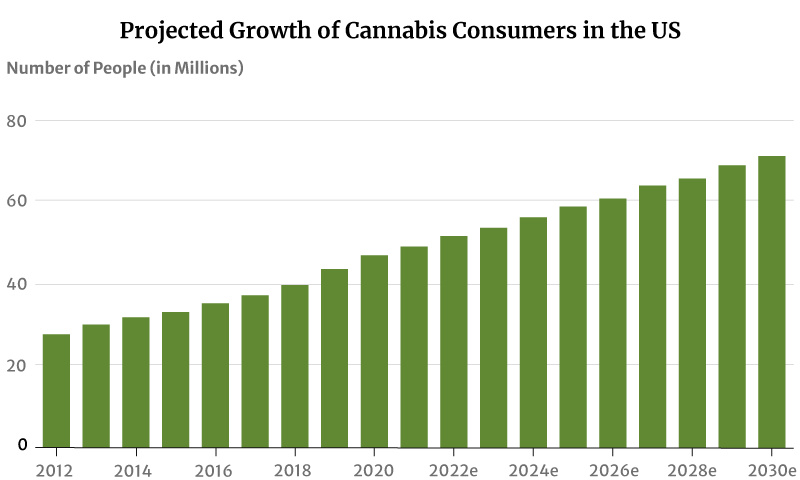

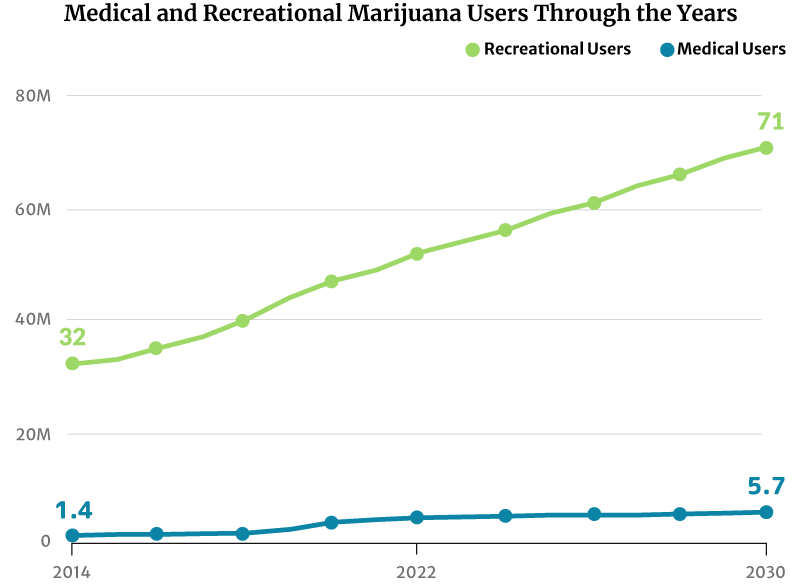

As for marijuana consumers, there had only been about 28 million marijuana users in 2012. This increased to 47 million in 2020. By the end of 2022, 52 million Americans will now have consumed cannabis [20].

If this trend continues, the number of people who use marijuana will increase to 71 million by 2030 [20].

What Age Group Smokes the Most Weed?

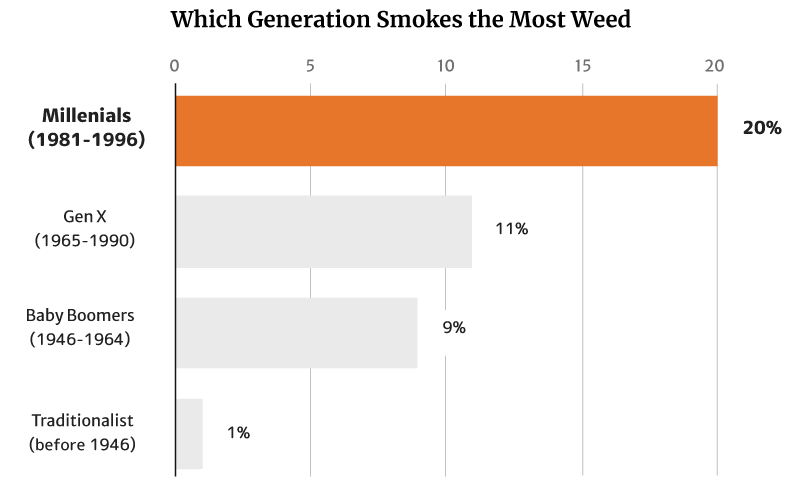

At 20%, it’s the millennials who smoke the most weed. They’re also the generation that consumes the most weed, making up 51% of the country’s cannabis consumers [12].

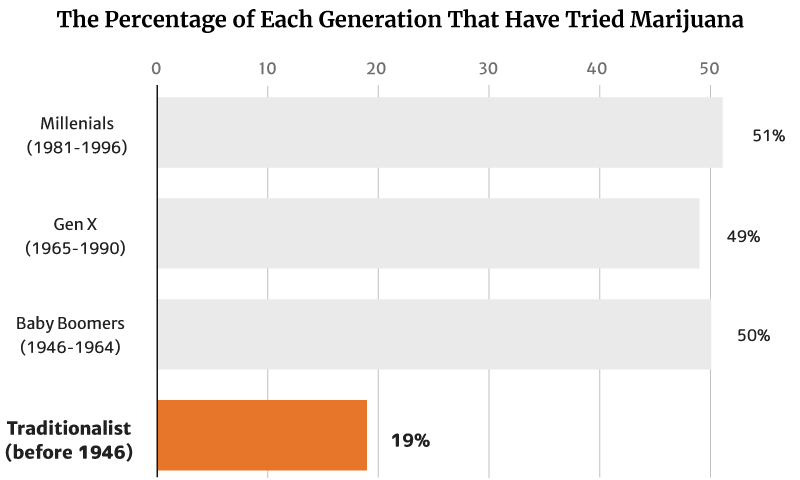

Gallup’s 2021 report showed that 45% of all American adults now have tried marijuana [12].

Of this percentage, millennials (1981 to 1996) make up the majority at 51%. Baby Boomers (1946 to 1964) follows at 50% [12].

Gen X (1965 to 1990) make up 49%, while the traditionalists (before 1946) make up the smallest percentage at 19% [12].

Of these numbers, it’s the young people who tend to smoke weed more, with 20% of Millennials making up the majority. This is followed by 11% of the Gen Xers as well as 9% of the Baby Boomers [12].

Again, it’s the Traditionalists who make up the smallest percentage at 1% [12].

When it comes to gender, 15% of adult men smoke weed than 9% of women [11].

Marijuana Use in Teens: How Many Teens Use Marijuana?

10.1% or 2.5 million American teens between 12 and 17 years old use marijuana illicitly, says the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) 2020 survey [31].

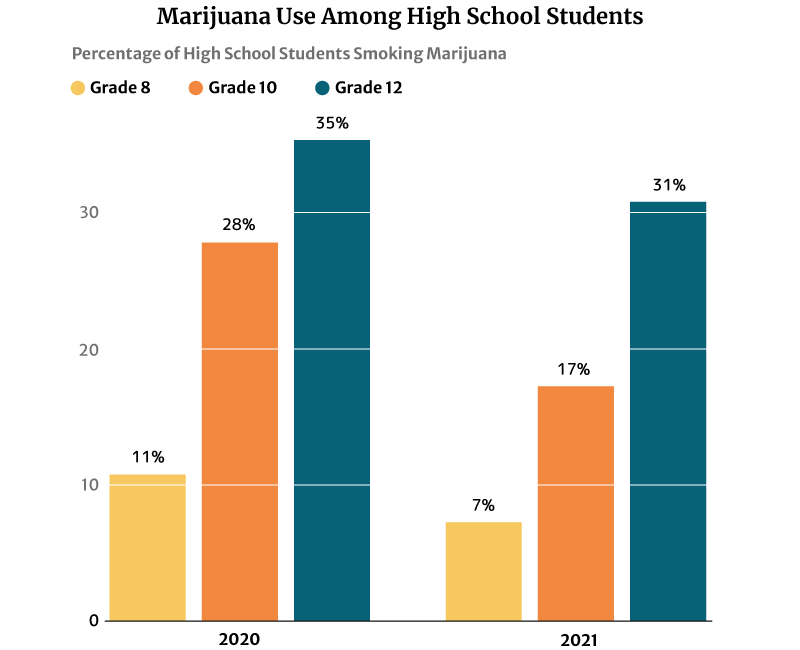

The 2021 report published on the National Institute on Drug Abuse website (NIDA) also notes that marijuana use is highest among 12th graders at 30.5%. However, this percentage has decreased from 2020’s 35.2% [21].

10th graders ranked second in marijuana users at 17.3%, a decrease in percentage from the 2020s at 28% [21].

Marijuana users among 8th graders also decreased from 11.4% in 2020 to 7.1% in 2021 [21].

Marijuana legalization, licensed dispensaries replacing drug dealers, and teens having a harder time obtaining illegal weed played a part in reducing their number, says a 2019 study published in Jama Psychiatry.

In states that have legalized recreational weed, there had already been an 8% decrease in the likelihood of minors trying marijuana [3].

Marijuana Use in College Students: How Many College Students Use Weed?

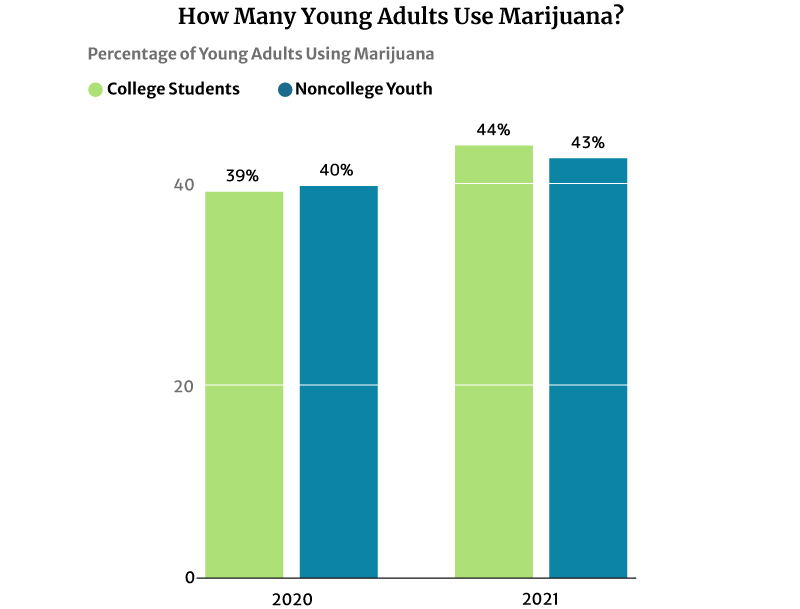

44% of American college students have used marijuana regularly in 2020. It’s a significant increase from 2016’s 39% says NIDA’s 2020 drug use survey [28].

43% of noncollege youth of the same age are also using marijuana in 2020. This percentage also increased from 41% in 2016 [28].

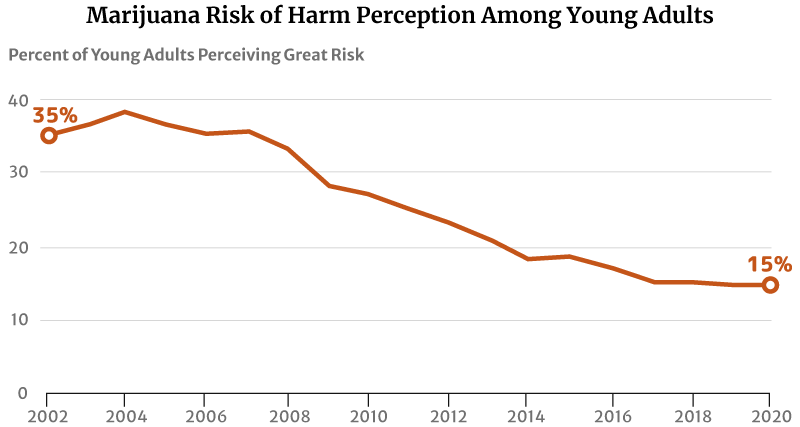

One factor that may have contributed to this increase is their reduced perception of marijuana’s risk of harm. The highest level was 75% in 1991 [29].

By 2002, only 35.5% of young Americans between the ages of 18 and 25 think regular marijuana use is harmful. This percentage has further decreased to 27% in 2010 and 14.8% in 2020 [13] [31].

What State Smokes the Most Weed?

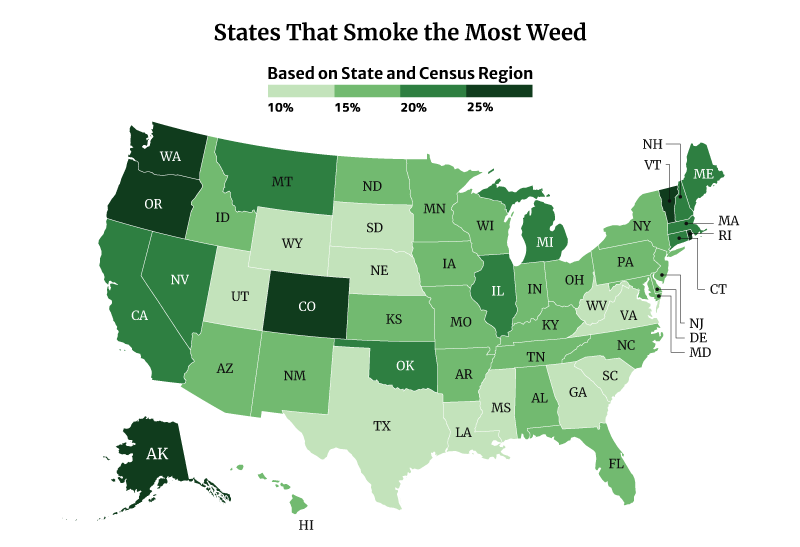

The District of Columbia smokes the most weed at 30.81%. Vermont at 30.15% and Oregon at 28.53% follows [22].

On the other hand, Texas smokes the least weed at 12.81%, followed by South Dakota at 13.42% and Virginia at 13.82% [22].

Among the regions, the West consumes the most weed at 22.70%, compared to the South at 15.14% [22].

How Much is the Weed Industry Worth?

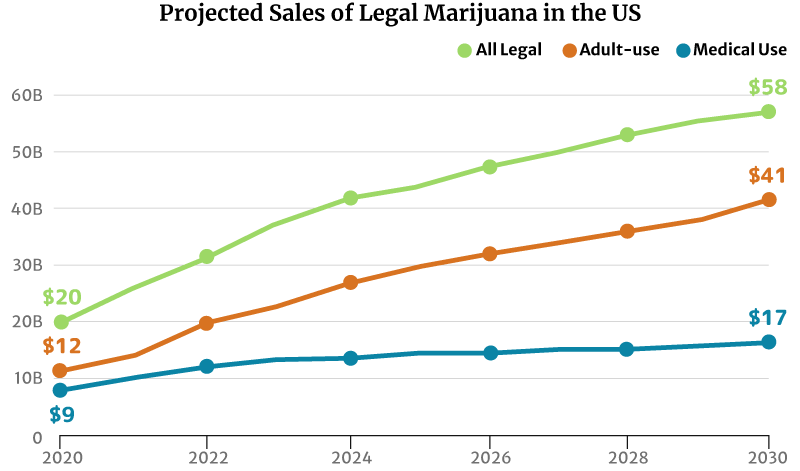

The legal marijuana industry in the U.S. is worth $27 billion in 2021. The recreational weed industry was at $15 billion, and medical cannabis was at $11 [20].

Related: CBD Statistics and Facts

By the end of 2022, the legal cannabis industry is projected to grow to $32 billion. Again, the recreational weed industry gets the largest market share at $20 billion. The medical cannabis industry trailed behind at $13 billion [20].

If the market trend continues, the legal marijuana industry could grow to $58 billion by 2030. The recreational weed market could grow double the medical cannabis industry’s at $41 billion and $17 billion, respectively [20].

Market analysts predict continued growth in marijuana sales. There will also be more marijuana consumers by 2030 [20]:

- From 32 million American people who use marijuana in 2014 to 71 million by 2030

- From 1.4 million registered medical marijuana patients in 2014 to 5.7 million by 2030

- From $20 billion in marijuana sales in 2020 to $58 million by 2030

Cannabis Sales Statistics: What State Sells the Most Weed?

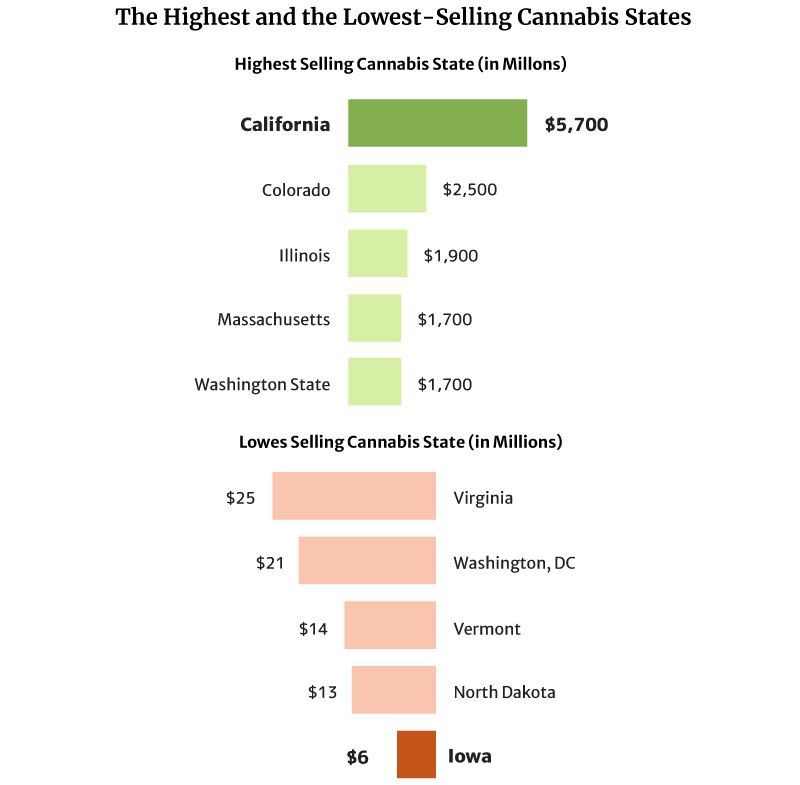

California sold the most weed in 2020 at $5.7 billion in 2020 [1].

Colorado also comes in second with $2.5 and Illinois with $1.9 billion [1].

The state with the lowest legal cannabis sales is Iowa, with $6 million. North Dakota with $13 million and Vermont with $14 million follow [1].

In total, cannabis sales in the U.S. reached $27 billion in 2021, a $7-billion increase from the 2020s of $20 billion [20].

Which Has the Highest Marijuana Revenue by State?

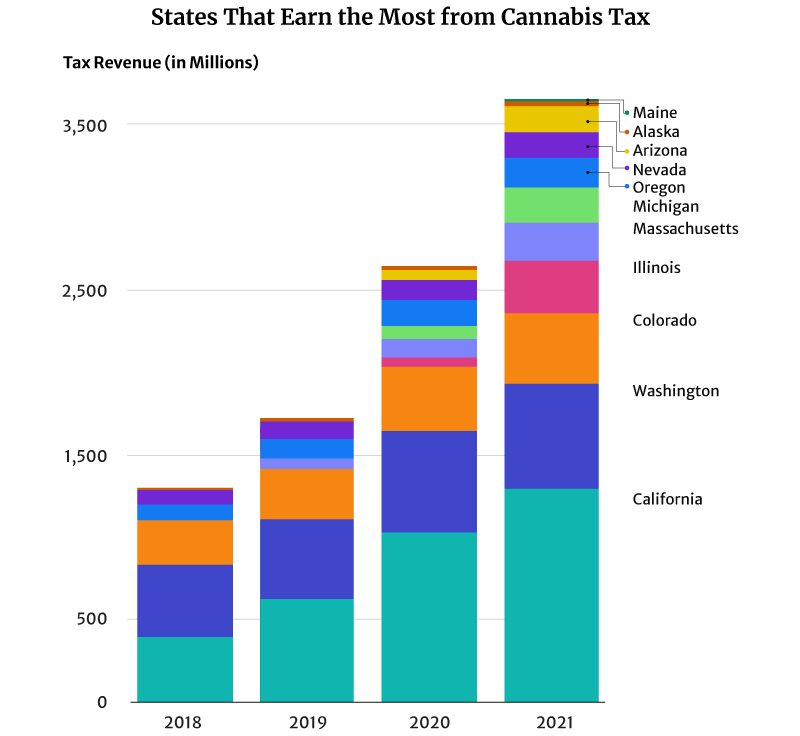

California had the highest marijuana revenue at $1.3 billion in 2021 [6].

Colorado comes in second place, earning one-third of California’s tax revenue at $423.5 million [15].

Illinois also earned $317.1 million in 2021, placing them in third place [4].

California’s younger cannabis market quickly overtook Washington and Colorado’s more matured market. Both states legalized recreational weed in 2012.

In 2018, for example, Washington was the top cannabis tax revenue earner at $437.2 million [25]. California at $397.7 million and Colorado at $266.5 million came in second and third places, respectively [6] [15].

By 2019, California’s $638.1 million tax revenue has overtaken Washington’s $477.3 million tax revenue [6] [25]. In 2020, California’s tax revenue breached the billion-dollar mark at $1.03 billion and $1.3 billion in 2021 [6].

Of all the U.S. states, Washington has the highest excise tax rate on recreational weed at 37%. With the addition of other taxes, this goes up to 46.2% [34]. The state’s legal cannabis sales are only one-third of California’s at $1.7 billion in 2020 [1]. By 2021, its marijuana tax revenue is almost half of California’s at $630.9 million in 2021 [25].

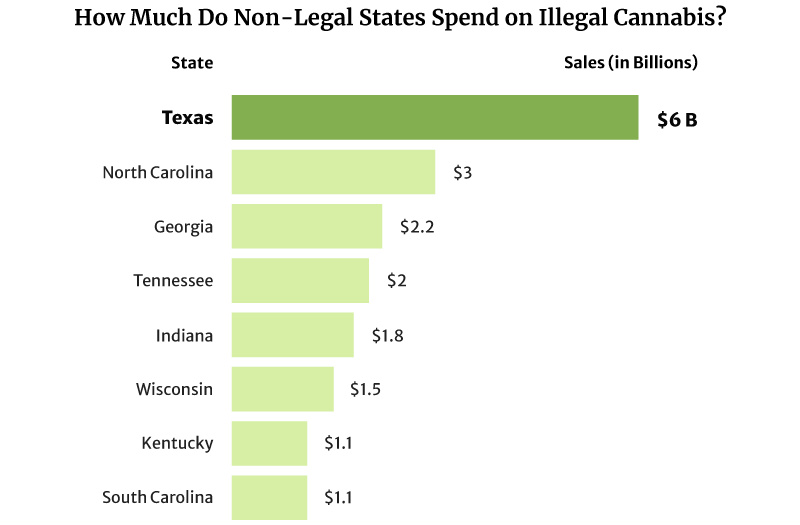

It comes as no surprise then that its illicit marijuana market is still thriving. In D.C., for example, its illicit marijuana market is worth $600 million in sales per year [17].

The illicit marijuana market is also thriving in states where weed is illegal. Texas spent as high as $6 billion on illicit marijuana in 2022, and North Carolina came in second at $3 billion [20].

Which State Has the Most Dispensaries?

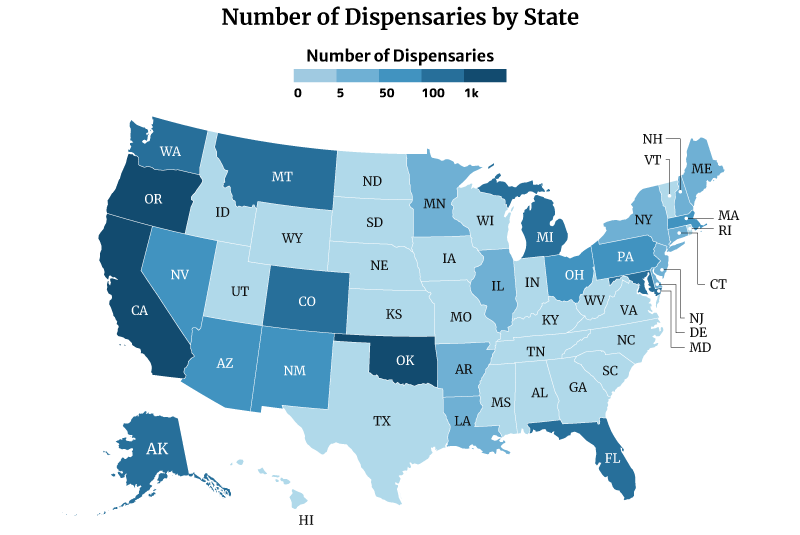

Oklahoma has the most dispensaries, with 2,129. California and Oregon follows with 1,440 and 1,344, respectively [10].

On the other hand, Missouri has the least number of dispensaries with one. This is followed by Rhode Island with three and New Hampshire and North Dakota with four [10].

What are the Average Dispensary Sales Per Day and Per Year?

On average, the sales of a regulated medical cannabis dispensary can reach about $8,219 daily. It can also earn $3 million annually [16].

Regulated recreational marijuana dispensaries and combo stores can earn about $4,932 daily. These shops can also earn $1.8 million yearly [16].

The unregulated medical marijuana dispensary’s daily sales reach about $2,027 per day. Yearly, it can earn $0.74 million [16].

Dispensaries that operate under a regulated legal weed market earn higher than unregulated dispensaries. One reason for this is the cap placed on the number of dispensaries that can operate per location. The cap lets them serve a bigger base of customers.

On the other hand, unregulated dispensaries earn less. They may be serving a large client base, but they’re also competing with more dispensaries, which eats away at their share.

Is the Average Dispensary Income Profitable?

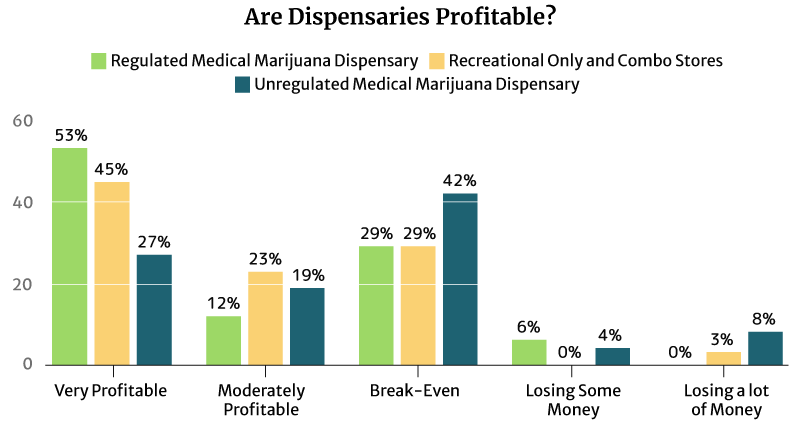

53% of the regulated medical cannabis dispensary owners say it’s very profitable, and so do 45% of the regulated recreational and combo marijuana dispensary owners.

12% of the regulated medical cannabis dispensary owners say it’s moderately profitable. 23% of the regulated recreational and combo marijuana dispensary owners also find their businesses moderately profitable [16].

An equal percentage (29%) of both types of regulated dispensaries say they’re just breaking even [16].

9% of the regulated dispensaries are either losing some money or losing a lot of money [16].

Again, it’s the unregulated dispensaries that seem to suffer the most [16].

- 42% say they’re only breaking even.

- 4% say they’re losing some money.

- 8% say they’re losing a lot of money.

Cannabis Industry Growth: Legalization Timeline from Medical to Recreational

It took California 20 years to legalize recreational weed in 2016. The state legalized medical marijuana use in 1996 [20].

Maine legalized medical marijuana use in 1999. It took the state 17 years to legalize recreational marijuana in 2016 [20].

Montana also took 17 years to legalize adult use. It approved marijuana for medicinal use in 2004 and adult use in 2021 [20].

The states with short legalization timelines are Massachusetts and Virginia.

It took Massachusetts four years to legalize recreational marijuana use in 2016. The state legalized medical cannabis in 2012 [20].

Virginia has the shortest legalization timeline of one year. The state legalized marijuana for medical use in the past year (2020). It also legalized recreational marijuana by the next year (2021) [20].

This isn’t true for all states though. Hawaii has been waiting for 22 years to legalize adult-use marijuana. It legalized marijuana for medical use in 2000. Delaware has also been waiting 11 years. The state legalized medical cannabis use in 2011 [20].

Marijuana Legalization Facts and Statistics

Four more states legalized recreational weed in 2021. Two states also approved the use of weed medically.

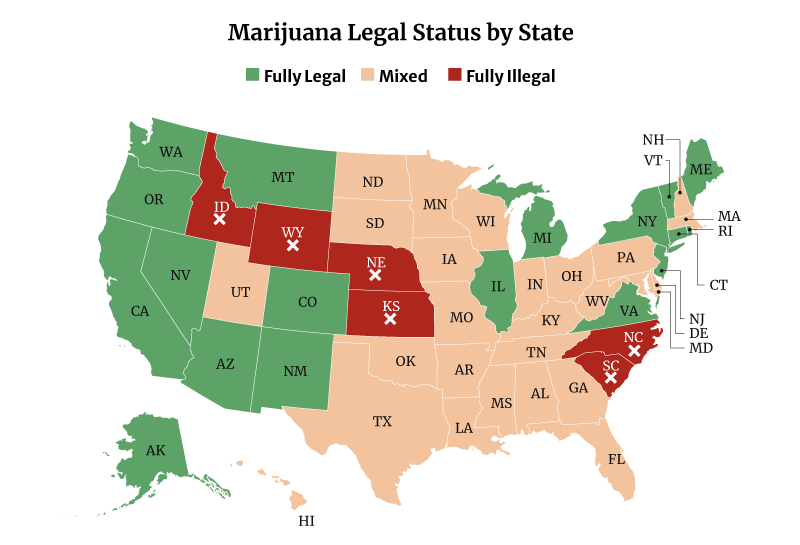

In all, 39 states have now legalized high-THC medical marijuana use. 19 states have legalized medical and recreational marijuana use. Both include the District of Columbia [20].

Related: States Where Weed is Legal

Only six states remain where marijuana is fully illegal, and these are [14]:

- Idaho

- Kansas

- Nebraska

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Wyoming

74%, 248 million, or nearly three-quarters of the United States 332.4 million population, now have access to some form of legal cannabis [19].

44% of American adults also now have access to legal recreational weed [20].

Only 26% or 89 million Americans live in states that still prohibit the use of any form of cannabis [20].

Before 2030, we’ll probably see nine more states legalizing adult-use marijuana. Nine more states might also legalize medical cannabis [20].

If this happens, it could mean giving 67 million more Americans access to legal weed. 74 million Americans will also have access to legal medical cannabis [20].

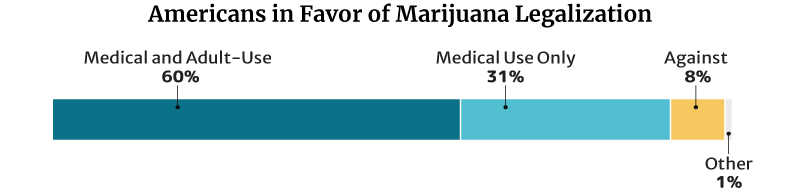

68% (17 in 25 Americans) believe that the federal government should legalize marijuana. This has doubled from 2001’s 34% [32].

This percentage is lower than the 2021 Pew Research Center survey. In their survey, 91% of American adults say they’re for the legalization of the herb [9]. This is a 50 percentage point increase from the 2010s 41% [23].

- Of the 91%, 60% say they’re for medical and recreational use. 31% say they’re for medical purposes only.

- 8% are against weed legalization.

Of note, marijuana is still illegal under federal law [7].

Medical Marijuana Statistics: How Many People Use Medical Marijuana in the U.S.?

4.4 million registered patients used medical marijuana in the U.S. in 2021. By the end of 2022, this will go up to an estimated 4.7 million [20].

Analysts project that the number of registered medical marijuana patients can go as high as 5.7 million by 2030. They would make up 2% of the country’s entire population [20].

What Do People Use Medical Cannabis for?

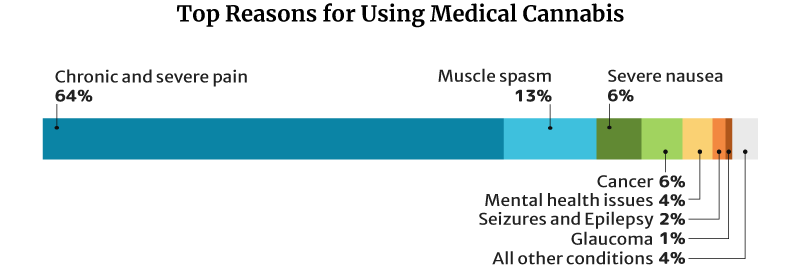

64.2% of medical cannabis patients use it for chronic and severe pain, similar to CBD and kratom. 13% use it for muscle spasms and 6.3% for severe nausea [18].

Is Medical Cannabis Effective?

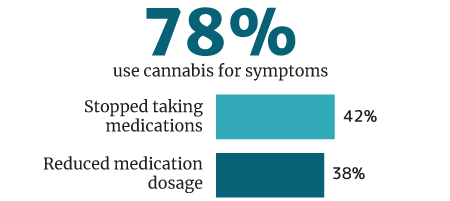

78% of cannabis users use it medically for symptoms and disease control, says a 2018 U.M. Institute for Social Research survey [33].

Of this percentage, 42% weaned themselves off of pharmaceutical medications. 38% say they reduced their intake of pharmaceutical drug use while being on medical cannabis [33].

What Do Americans Think of Medical Cannabis?

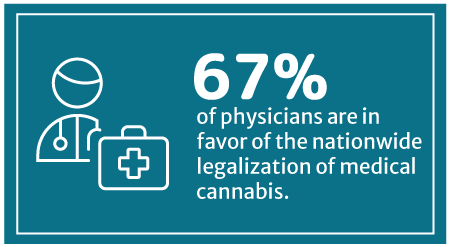

67% of physicians are now in favor of nationwide medical cannabis legalization, says a 2018 Medscape poll [8]. Medscape is a part of the WebMD Health Corp.

This percentage has increased from WebMD’s 2014 survey, which showed that 56% approve of legalizing medical cannabis on a federal level [24].

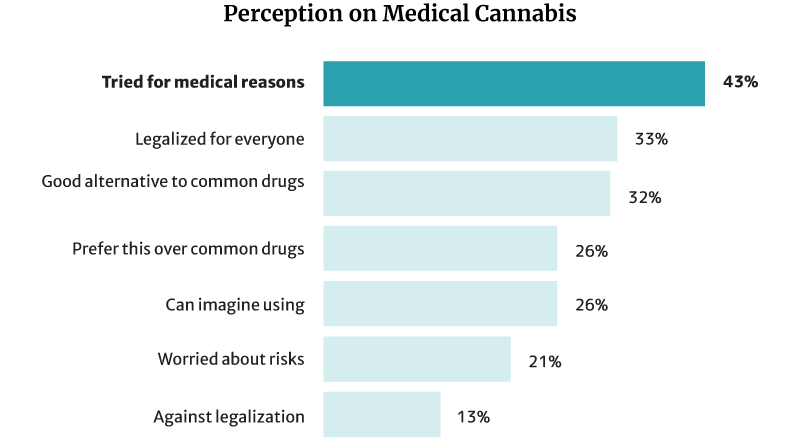

43% of Americans have already tried cannabis and CBD for medical reasons. Of this percentage [26]:

- 32% say it’s a good alternative to pharmaceutical and traditional medical products.

- 26% say they would choose it more than chemical medications.

Cannabis Trends During the COVID19 Pandemic

Marijuana sales increased by 38% in several states in March 2020, compared to January’s first full week of the same year. Cannabis sales peaked by the end of August 2020, increasing by 59% compared to January 2020’s first week [27].

Because marijuana was considered essential during the pandemic, consumers needed a way to get their supplies. This gave rise to curbside pickups, drive-through options, and online preorders.

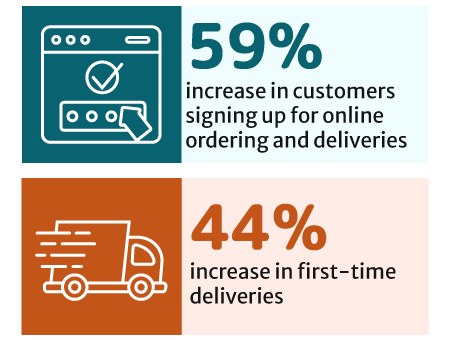

New customer sign-ups for online ordering and delivery increased by 59%. There has also been a 44% increase in first-time deliveries [30].

For some dispensaries, online transactions made up 90% of their marijuana sales. In-person sales made up only 10% [27].

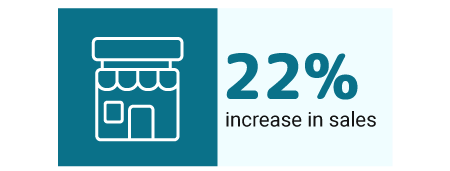

Cannabis stores that offered preorders enjoyed a 22% increase in sales. Those that didn’t offer the preorders failed to enjoy the same benefits. [5].

There has also been a change in the cannabis consumption trend.

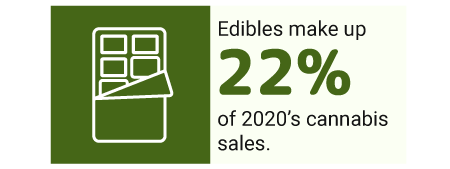

The COVID19 virus affected the lungs more. Because of this, more cannabis consumers switched from smoking marijuana to edibles. This made edibles the top choice among cannabis products. By the time 2020 ended, edibles had already made up 22% of all marijuana sales [30].

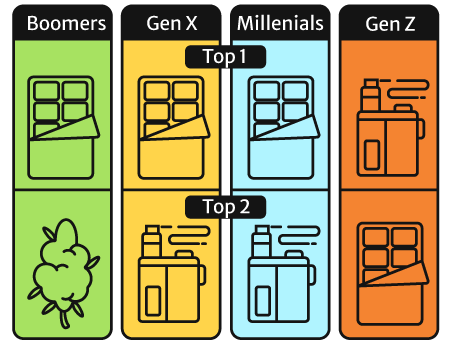

Edibles became the top choice across all age groups, too, except for the Gen Zs.

People belonging to this age group still prefer their vapes to edibles, flowers (cannabis Sativa and cannabis Indica plant), and pre-rolls [30].

Will These Cannabis Trends Continue?

By the end of 2020, cannabis sales have gradually slowed down to pre-pandemic levels. However, some trends continued [2].

- Marijuana delivery and curbside pickup were about equal in 2020’s first half. However, the first half of 2021 showed that more consumers are now in favor of cannabis delivery. Cannabis delivery made up 60% of 2021’s orders, compared to 2020s 40%.

- Cannabis deliveries increased by 97% compared to 2020’s first half.

Edibles may have gained popularity during the pandemic. However, cannabis flowers still remained the popular choice. It made up 50% of the whole cannabis sales in January 2022 [20].

What’s the Future of the U.S. Cannabis Industry?

The future of the country’s marijuana industry seems pretty rosy [20].

- The legal medical cannabis industry could increase from $9 billion in 2020 to a $17 billion industry by 2030.

- The legal recreational industry could grow from $20 billion in 2020 to a $58 billion industry by 2030.

Final Thoughts — U.S. Marijuana Industry Outlook

We can expect the country’s legal marijuana industry to continue growing. The number of medical and recreational cannabis consumers is expected to grow in the coming years. In time, weed will become a part of daily life. Marijuana sales are up. Support for marijuana legalization on a federal level has also increased.

Social acceptance has risen as well. There are now more states with some form of legal marijuana than states where it’s fully illegal.

If market prediction stays true, the country’s legal marijuana market could easily become a $58 billion to $72 billion industry [20].

References

- 2021 Annual Marijuana Business Factbook. (2022). Marijuana Business Daily. [1]

- 2021 Cannabis in America. (2022). Weedmaps. [2]

- Anderson, D. M., Hansen, B., Rees, D. I., & Sabia, J. J. (2019). Association of Marijuana Laws With Teen Marijuana Use. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(9), 879. [3]

- Annual Report Fiscal Year 2021. (2021). Illinois Department of Revenue. [4]

- Cannabis, COVID-19, and Beyond. (2020). State of the Cannabis Industry. [5]

- Cannabis Tax Revenues. (2022). California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. [6]

- Drug Fact Sheet: Marijuana/Cannabis. (2020). Drug Enforcement Administration. [7]

- Frellick, M. (2018). Medical, Recreational Marijuana Should Be Legal, Most Clinicians Say. Medscape Medical News. [8]

- Green, T. V. (2021). Americans overwhelmingly say marijuana should be legal for recreational or medical use. Pew Research Center. [9]

- Hobson, K. (2021). Cannabis Dispensaries Growth Study 2022. Kisi. [10]

- Hrynowski, Z. (2020). What Percentage of Americans Smoke Marijuana? Gallup, Inc. [11]

- Jones, J. M. (2021). Nearly Half of U.S. Adults Have Tried Marijuana. Gallup, Inc. [12]

- Lipari, R., Kroutil, L. A., & Pemberton, M. R. (2015). Risk and Protective Factors and Initiation of Substance Use: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). [13]

- Map of Marijuana Legality by State. (2022). Disa. [14]

- Marijuana Tax Reports. (2022). Colorado Department of Revenue. [15]

- McVey, E. (2017). Marijuana Business Factbook 2017. Marijuana Business Daily. [16]

- Medical Marijuana Patient Access. (2022). District of Columbia Council. [17]

- Medical Marijuana Patient Breakdown by Qualifying Medical Condition. (2016). [Bubble Chart]. Marijuana Business Daily. [18]

- Moore, D. (2021). U.S. Population Estimated at 332,403,650 on Jan. 1, 2022. United States Census Bureau. [19]

- Morrissey, K., Reiman, A., Tomares, N., & Adams, J. (2022, March). 2022 U.S. Cannabis Report. New Frontier Data. [20]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2021). Percentage of adolescents reporting drug use decreased significantly in 2021 as the COVID-19 pandemic endured. National Institutes of Health (NIH). [21]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (2020). 2019-2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Prevalence Estimates (50 States and the District of Columbia). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). [22]

- Public Support For Legalizing Medical Marijuana. (2010). Pew Research Center. [23]

- Rappold, R. S. (2014). Legalize Medical Marijuana, Doctors Say in Survey. WebMD. [24]

- Recreational and medical marijuana taxes. (2022). Washington State Department of Revenue. [25]

- Richter, F. (2021). What Americans Think About Medical Cannabis. Statista. [26]

- Schaneman, B. (2022). How the US cannabis industry weathered two years of pandemic upheaval. Marijuana Business Daily. [27]

- Schulenberg, J. E., Patrick, M. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Miech, R. A. (2021). National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2020. National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2. [28]

- Sherburne, M. (2021). Daily marijuana use among US college students reaches a new 40-year high. Michigan News (University of Michigan). [29]

- State of Cannabis 2020. (2021). Eaze Technologies, Inc. [30]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [31]

- Support for Legal Marijuana Holds at a Record High of 68%. (2021). Gallup, Inc. [32]

- Wadley, J. (2019). Many users prefer medical marijuana over prescription drugs. Michigan News (University of Michigan). [33]

- Washington state adult-use cannabis generates huge impacts, but the tax burden is high. (2022). Marijuana Business Daily. [34]

- Cannabis & Kratom: What’s The Difference? Can They Be Mixed? Kratom.org [35]